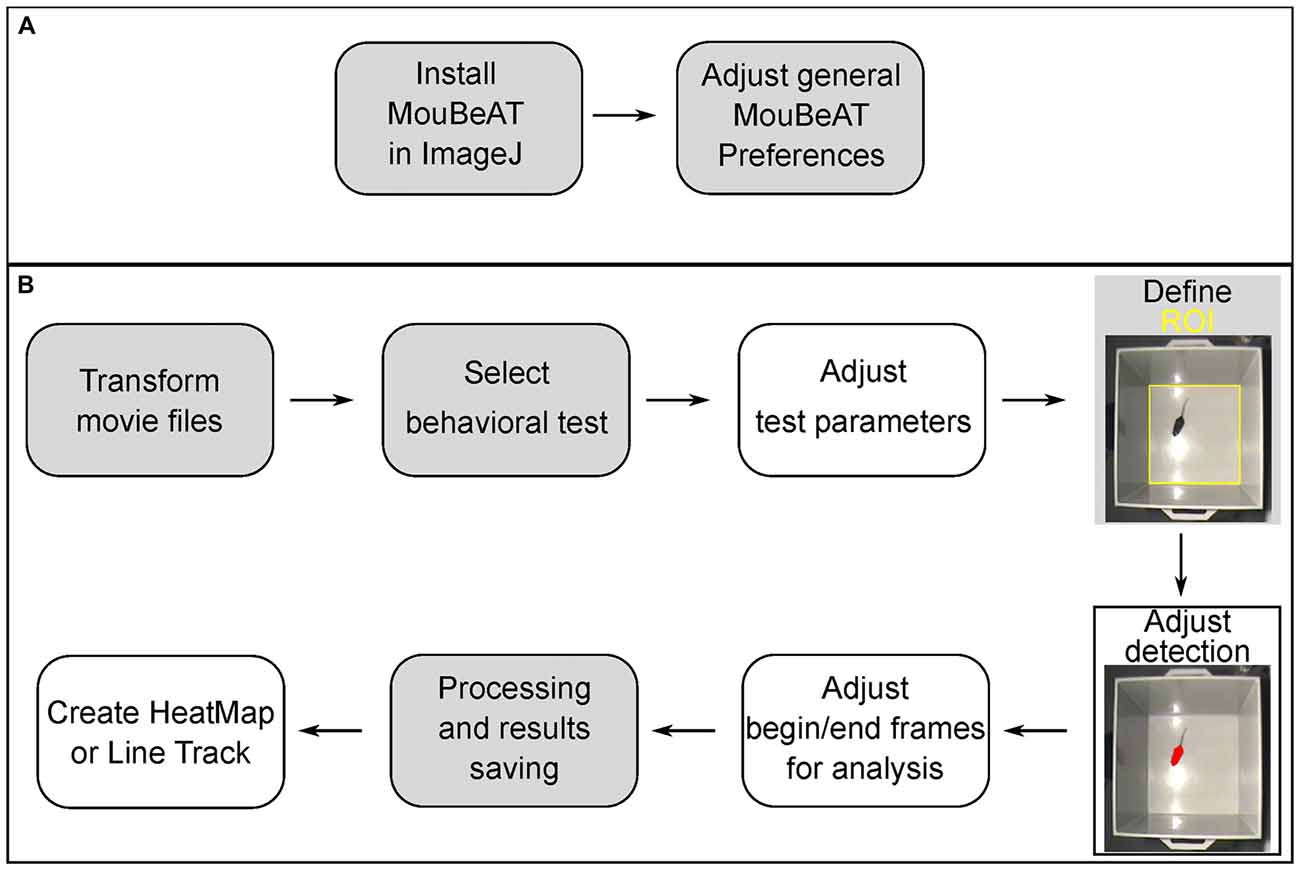

“It can’t really attend to the task.”Īlternatively, an animal might be lethargic, or exhibit repetitive behaviors such as jumping neither state is conducive to social interaction. “If the animal is really hyper and just running around the box, of course you’ll get reduced social interaction,” says Stacey Rizzo, director of the Mouse Neurobehavioral Phenotyping Facility at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. “There is no set number of seconds that means social,” Silverman says.įor example, a mutation might lead to unpredictable changes in an animal’s base level of activity, which would affect the amount of time spent with another mouse. The reason is that the absolute time spent can vary depending on mouse strain, sex and unpredictable factors, such as the effects of an engineered mutation. Researchers must not compare the amount of time a mutant animal and a control mouse spend with the unfamiliar mouse to conclude that one is less social than the other, or say that an experimental drug made an animal more social than it was before. This is a strictly binary measure, Silverman says: All it can reveal is whether a mouse prefers another mouse to an object. Only mice that spend more time with the novel mouse are classified as appropriately ‘social’ creatures. The testing apparatus consists of three chambers: a central space, a chamber on one side that includes an unfamiliar mouse under a mesh cup, and a chamber with a mesh cup that may either be empty or contain an object.Īfter giving the test mouse 10 minutes to acclimate to the apparatus, researchers place it in the middle chamber and track where it spends the following 10 minutes. Social creatures :Īn activity called the ‘three-chambered social approach task’ assesses sociability in mice and is frequently used to characterize mouse models of autism risk genes.

#ANY MAZE OPEN FIELD BEHAVIORAL TESTING HOW TO#

We spoke with autism researchers schooled in mouse behavior about what can go wrong with the tests - and how to avoid those traps. “It’s usually when someone makes a new genetic model or has a new treatment that they think could now come into this space.” “In high-impact papers, I see frequently, maybe 50 percent of the time,” says Jill Silverman, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis. Many scientists conduct or interpret them incorrectly, and the problems then taint the literature.įor example, researchers often incorrectly gauge sociability, and they frequently fail to account for how repetitive behaviors caused by a mutation might affect performance on behavioral tasks.

Tests for unusual behavior in mice are notoriously prone to operator error.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)